California received some much-needed precipitation in March and April, a reprieve from a winter of clear skies, but it was not enough to head off the state’s expanding drought.

In its final snow survey of the season, the California Department of Water Resources reported the Sierra snowpack is only 37% of the average for this date, meaning the prospect of drought continues to loom over the state.

“March and April storms brought needed snow to the Sierras, with the snowpack reaching its peak on April 9, however, those gains were not nearly enough to offset a very dry January and February,” said Sean de Guzman, who runs the survey for Department of Water Resources.

The lack of water this time of year is particularly daunting for decision-makers as weigh how much water to release to the thirsty farms that dot the Central Valley in one of the nation’s most productive breadbaskets.

The snowpack in the Sierra provides the state with about 30% of its water during an average year, as it slowly melts and replenishes the system of reservoirs and water storage facilities during the dry months of May through October.

For the water year that began in October 2019, it wasn’t just a lack of precipitation, but an increase in temperatures throughout the Sierra during the springtime.

“The last two weeks have seen increased temperatures leading to a rapid reduction of the snowpack,” Guzman said. “Snowmelt runoff into the reservoirs is forecasted to be below average.”

After little to no precipitation at the beginning of the water year, things started rolling with a series of large storms in December that stoked optimism for another above-average year of rain and snow in California. But as so often happens, the spigot turned off in January and while a few late-season storms help defray total disaster, they were not enough to get the state even close to average.

At Phillips Station just south of Lake Tahoe, scientists measured a paltry 1.5-inch snowpack, which is only 3% of average. Measurements taken throughout the entire mountain range painted a slightly rosier picture but fall well short of ideal.

The six largest reservoirs are in good shape for this time of year, with the lowest at 83% of average and the highest at 126% of average.

Lake Shasta, the largest surface-area reservoir in the state, is at 94% of its historic average and at 83% of capacity. California can withstand a dry season, but when they line up consecutively, water conditions can quickly turn dire as happened last decade with a five-year drought.

Drought has already started to appear in parts of the state.

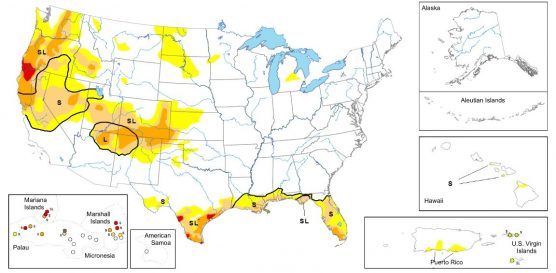

Up north along the California-Oregon border, extreme drought has taken hold of a large swath of land, where stream flows are low and grasslands are drying out quickly, presenting challenges for livestock grazers, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

“Most of the western U.S. received little to no rain, except for small pockets of the Pacific Northwest and the Southwest,” the drought monitor said in its weekly report released on Thursday.

Severe drought expanded around Portland, Oregon, and moderate drought expanded throughout much of the West Coast, including Northern California.

Drought-like conditions continued to prevail in the eastern portion of Washington state and Oregon, with the leeward side of the Cascades experiencing sustained periods of dry weather.

The Four Corners region of the U.S. Southwest is also entering the summer period without much precipitation, meaning a long-term drought trend could persist into the near future.

Moderate drought also crept into Nevada, particularly the central part of the state.

Yet California, with its thin snowpack and huge water demand, continues to have the most land categorized in the range from abnormally dry to extreme drought.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.