What is a Tataviam home called? That was a topic of much discussion at the Placerita Canyon Nature Center for about 20 years. As the local Tataviam Indians did not have a written language and did not leave us with a specific word for their “home sweet home,” we have worked our way through many options over the last 20 years.

What is a Tataviam home called? That was a topic of much discussion at the Placerita Canyon Nature Center for about 20 years. As the local Tataviam Indians did not have a written language and did not leave us with a specific word for their “home sweet home,” we have worked our way through many options over the last 20 years.

The words hut, shelter, ki’j, ap, wikiup and Indian dwelling have been used, even embraced with enthusiasm, only to be abandoned a few years later. However, it seems the word “wikiup” would have been used in Nevada and Arizona, and “ap” would have been a term used by Chumash tribes; but the word “ki’j” was used by the Tataviam, according to some experts in the field. Since my aim is to educate and not to offend, I may use the general terms “shelter” or “dwelling” here. That will come handy if the pronunciation of “ki’j” somehow escapes you.

What is a ki’j? It is a domed wooden frame covered with tall grass that has been gathered into bundles. In the traditional way, willow poles are set in the ground in a circle, poles are bent to form a dome, small branches are cut and tied crosswise to complete the framework, and sedge bundles are attached to the frame.

The Tataviam were hunter-gatherers, so the majority of their time was spent finding food and cooking it. It was a hard life, working every day for basic survival. They would build a new hut each year, moving it to another spot the following year. They came to Placerita Canyon to gather acorns but did not actually live there.

The Tataviam were hunter-gatherers, so the majority of their time was spent finding food and cooking it. It was a hard life, working every day for basic survival. They would build a new hut each year, moving it to another spot the following year. They came to Placerita Canyon to gather acorns but did not actually live there.

A more reliable source of water than found in Placerita was important to sustain their lifestyle. Their dwellings were located around the Santa Clara River and in Newhall.

The Tataviam came to Placerita Canyon to gather acorns that were a staple of life for them, something that was cooked on a daily basis and would sustain them for the rest of the year. The crop picked in the fall was very important for their survival, and it is probable that small shelters were built to accommodate their families during that gathering time.

We have an example of a ki’j at Placerita, originally built many years ago by Jacob Sweany as an Eagle Scout project. He constructed it under the supervision of Frank Hoffman, recreation services supervisor at the park. The rebar used instead of wood for the frame was hidden by mule fat, and willow and twine cloth was used to resemble the twine made by the Tataviam with yucca fibers. Hoffman wanted to keep the dwelling authentic, but it needed to be refurbished every year, just as the Tataviam would have done.

We have an example of a ki’j at Placerita, originally built many years ago by Jacob Sweany as an Eagle Scout project. He constructed it under the supervision of Frank Hoffman, recreation services supervisor at the park. The rebar used instead of wood for the frame was hidden by mule fat, and willow and twine cloth was used to resemble the twine made by the Tataviam with yucca fibers. Hoffman wanted to keep the dwelling authentic, but it needed to be refurbished every year, just as the Tataviam would have done.

Fresh sedge or tule needed to be cut in the spring and attached in small bundles to cover the frame to make a cover over the hut. The sedge could be cut only early in the spring when it is very pliable, enabling it to be bundled and attached. Where could we find this kind of soft sedge?

Years ago, the Nature Center at Whittier Narrows was able to flood part of its land with reclaimed water, and ample fresh sedge grew there. But it took three truck beds full to be able to make a fresh cover for the ki’j. This proved to be a project impossible to sustain on a yearly basis when Whittier Narrows Nature Center was not able to flood its area any more, and we ran out of fresh sedge.

Frankly, it was a project that was taking so much time and effort that we became discouraged. So the hut lay naked and forlorn for many years.

The ki’j seen at Placerita is small and accommodates just two people. Most of the time, ki’j were much larger, built to accommodate all of the members of an extended family. These were typically 12 to 20 feet across. The chief of the tribe usually had the largest ki’j, up to 35 feet across.

The ki’j seen at Placerita is small and accommodates just two people. Most of the time, ki’j were much larger, built to accommodate all of the members of an extended family. These were typically 12 to 20 feet across. The chief of the tribe usually had the largest ki’j, up to 35 feet across.

Although most cooking was done outdoors, a hole was still left open in the roof for ventilation because if it was cold or rainy, a fire would be lighted inside and the smoke would escape through the opening. If it rained, the hole would be covered with a deer skin during the night to protect the sleeping family.

The opening for the door was always made on the southeast side for protection from the cold wind coming from the north. Deer skin was draped above the door to further keep the inside warm and cozy. In this respect, the ki’j at Placerita is not positioned according to Indian tradition, but we wanted visitors coming along the trail to be able to see into the inside of the dwelling.

When a ki’j was completed, it was celebrated with a small ceremony where sage was burned inside. It was a ceremony to consecrate the new home, but often those traditions are backed up by a strong, down-to-earth purpose. In this case, the sage smoke was useful as a disinfectant, killing many of the insects hidden in all of those fresh construction materials.

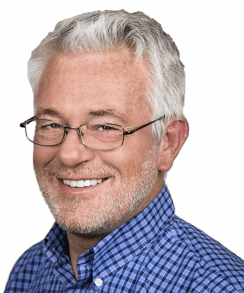

Denny H. Truger, a volunteer at the Placerita Canyon Nature Center, saw the remnants of the Tataviam hut during his docent training in 2012. Only the rebar remained standing, and it was a sad sight that stuck in his mind. Recently retired, Denny finally had some free time and decided something needed to be done to put the ki’j back in shape and make it once again a useful teaching tool, helping visitors to learn about the lives of the Tataviam in Placerita all those many years ago.

Denny H. Truger, a volunteer at the Placerita Canyon Nature Center, saw the remnants of the Tataviam hut during his docent training in 2012. Only the rebar remained standing, and it was a sad sight that stuck in his mind. Recently retired, Denny finally had some free time and decided something needed to be done to put the ki’j back in shape and make it once again a useful teaching tool, helping visitors to learn about the lives of the Tataviam in Placerita all those many years ago.

How do you start such a project? Since their ki’j had to last only one year, the Tataviam did not have to build something super strong. But Denny’s requirements were different. Denny wanted the ki’j to be strong and sturdy, plus accurate, at least in its basic shape.

Denny visited several museums to gather information and learned many facts about the ki’j in this process. The most help he received was from Graywolf at the Chumash Indian Museum in Thousand Oaks, and Denny is grateful for his active participation in the project.

Gathering sedge was not an option, and it had been the stumbling block from the start. Graywolf was the one who recommended a covering which has the same appearance, but which is actually manufactured and can be ordered by the roll. Problem solved for many years to come.

The rebar needed to be repaired by welding, and that is not a simple project in a natural area where the fire danger is so great. All of the requirements for safety were observed, and the preparation took the most time, but the welding was done to everyone’s satisfaction.

The rebar needed to be repaired by welding, and that is not a simple project in a natural area where the fire danger is so great. All of the requirements for safety were observed, and the preparation took the most time, but the welding was done to everyone’s satisfaction.

The thatched covering was attached to the dome, and the new ki’j looks good indeed. Denny worked carefully and diligently along with his team: Andrea and Mike Donner, Maria Elena Christensen, Mike Summe, Robert Grzesiak and Dan Kott. Thanks to all of them for their help.

Denny Truger

Denny is in the process of having an interpretive sign installed next to the ki’j to explain about the dwelling and about the people who would have used it. He wants it to give some basic information about the Tataviam Indians so our visitors can learn about and appreciate the lives of this local tribe that used to visit Placerita, including how important this place was for them.

Thank you to Denny Truger for making a visit to Placerita Canyon even more educational today. I hope the story of the ki’j will interest you enough to come by for a nice hike in Placerita Canyon and a look into our area’s colorful past as you take a short rest by our Tataviam ki’j.

Evelyne Vandersande has been a docent at the Placerita Canyon Nature Center for 28 years. She lives in Newhall.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

1 Comment

Thank you to Mr. Truger and his team! The nature center was always a favorite destination for my kids when they were growing up, and I hope a new generation of children will appreciate the ki’j and learn how families used to live.

One question, though. Is the apostrophe in “ki’j” absolutely necessary? Inquiring Scrabble players would like to know.