Read an update to this story here => http://scvnews.com/?p=32325

One man’s wilderness is another man’s playground.

Thus begins the battle for the future of some of Southern California’s last remaining roadless natural areas.

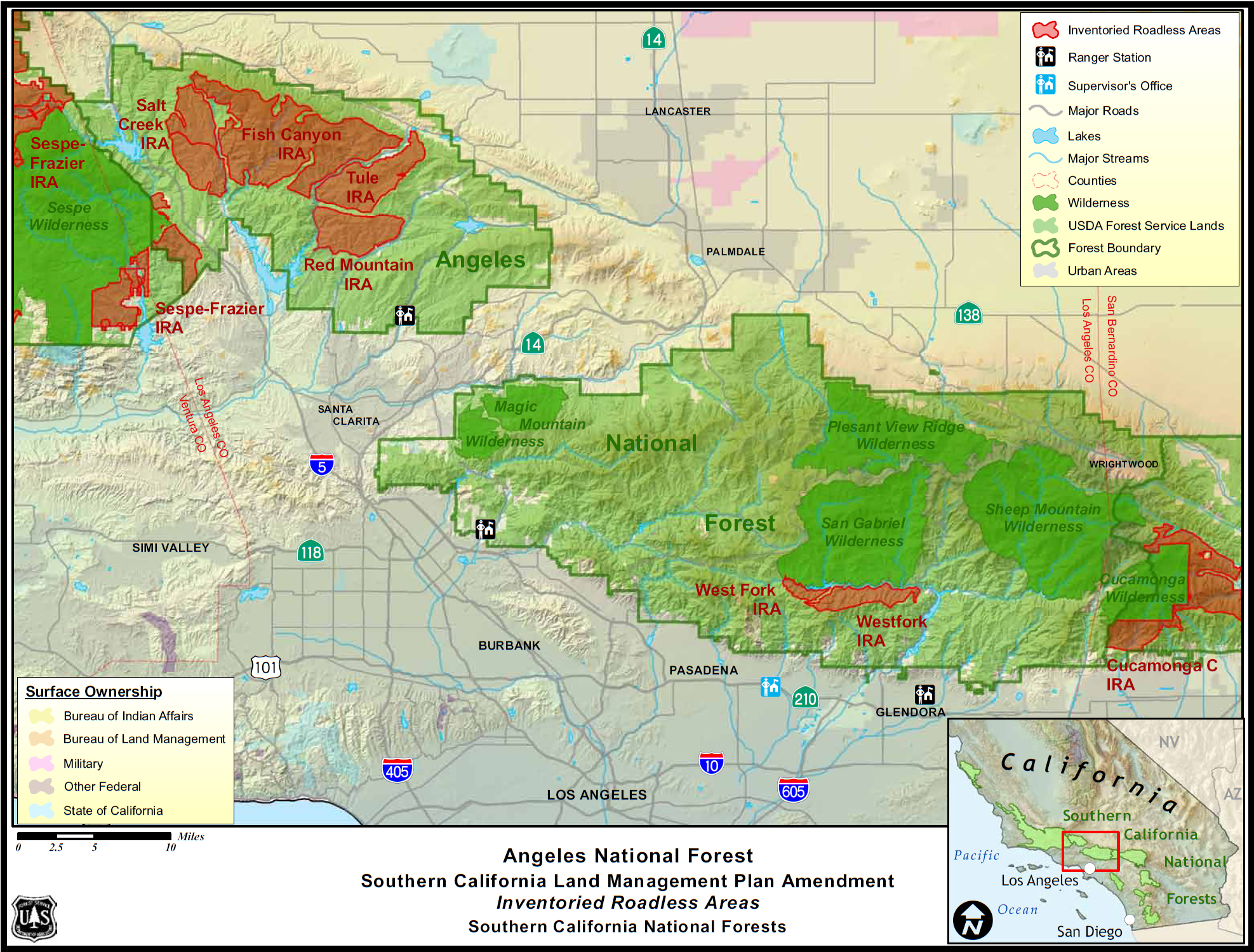

Local residents have until Monday, June 11, to tell the Forest Service whether mountain bikes and other non-motorized vehicles – and for that matter, motorized vehicles – should be formally banned from a canyon north of Castaic Lake and other federal lands in Southern California.

It’s the latest development in a legal feud between the state and federal governments that dates back several years.

– – –

On Feb. 28, 2008, California Resources Sec. Mike Chrisman and then-Attorney Gen. Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown Jr. filed a complaint in federal court, accusing the U.S. Forest Service of disregardingCalifornia’s land management plans for the Angeles, Cleveland, Los Padres and San Bernardino National Forests and thus putting these areas at increased risk.

“Time and again we have tried to hold the Forest Service to their word on the roadless policy. Time and again they have failed to live up to their promises,” Chrisman said at the time. “Following months of trying to work with them and establish what we believe to be reasonable management plans for Southern California’s forests, we were afforded no alternative but to file suit.”

“Plaintiffs alleged violations of several federal laws including the National Forest Management Act, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and Administrative Procedure Act,” said Justin Seastrand, environmental coordinator for the Angeles National Forest.

The lawsuit followed nearly three years of ill-feeling between the Forest Service and California’s environmental groups and elected officials.

In January 2005, the California Resources Agency wrote a letter to Jack A. Blackwell, regional U.S. Forester, noting that the Forest Service’s interim directive regarding the inventoried roadless areas (IRAs) would expire the following year. The state asked the feds to reevaluate its land management plans, specifically requesting that the Forest Service update its area maps to reflect the true condition of the IRAs, allow access to native American tribes en route to sacred sites within the forests, provide appropriate access to fire fighting crews, and reexamine whether the roads in those areas should be decommissioned or further maintained.

Chrisman’s letter stated, “We believe that California’s best interests are served when truly roadless areas remain roadless. However, unlike wilderness areas, a multitude of activities are allowed in roadless areas so long as new roads are not created for such activities.”

Blackwell’s response was encouraging. He agreed with all of Chrisman’s propositions, and in 2006 the Forest Service withdrew its original land management plans for the four Southland forests.

However, in a letter of March 15, 2006, to Bernard Weingardt, the Pacific Southwest Region’s forester, Chrisman had to reiterate his request to address the designations in the four forests.

At stake was a combined managed area of more than 4 million acres of Southern California forest, hundreds of thousands of which the state and the environmental groups fought to keep pristine. That is a big bounty for anyone.

So they launched a legal war.

Then-Gov. Schwarzenegger wrote to U.S. Agriculture Sec. Mike Johanns, saying he wished Johanns would realize California wasn’t about to give up the fight for its wilderness areas.

“Frankly, it is not too much to ask the Forest Service to do the right thing and live up to its own assurances,” Schwarzenegger’s letter stated.

The response from the Forest Service was cordial but vague. While the feds pledged their commitment to the “4.4 million acres of inventoried roadless areas in the state of California,” they also stopped short of committing to their complete protection.

“I believe the best way to resolve concerns over the protection of California’s inventoried roadless area is through cooperatively developed state-specific rule making,” Johann wrote. However, he said he believed the department’s 2005 rule was “properly promulgated” and would “assure conservation and management of inventoried roadless areas.”

“Accordingly,” Johann wrote, “we are pursuing an appeal to the ruling of the District Court.”

So it snowballed.

Between the 2008 court filing and 2011 when the settlement was finalized, the various litigants were fighting tooth and nail for what they thought the people wanted: On one hand, the 4×4, OHV and mountain biking communities argued that the national forests were created for multiple uses, ergo they had just as much right to be on the trails as the “foot people.” On the other side were the hikers, naturalists and conservationists pursuing an age-old goal: keep nature natural.

– – –

“Wilderness has to be land that is exceptional and not trammeled by man,” says Dianne Erskine-Hellrigel, executive director and president of Santa Clarita’s Community Hiking Club. “In other words, if man has left scars behind, it is most probably not suitable.”

“I hike because I enjoy the solitude,” she said. “This is why I appreciate wilderness. These areas that are recommended for wilderness provide that peace that I seek. Wilderness also brings us better quality water and air.”

The mountain biking community couldn’t agree more. Their issue is not with the existing – and arguably plentiful – wilderness areas of the Southland, which they enjoy as much as the hikers or equestrians do, but rather with the reasoning behind the restrictions of the new land management plan.

“I’m not in favor of the federal policy of prohibiting all mountain biking in all federal wilderness areas,” said Santa Clarita resident Ed Pongracz. “These are public lands, and I and my fellow mountain bikers have as much right to explore these lands on my non-motorized bicycle as does someone else with their horse or hiking boots and trekking poles.”

“Studies show that the impacts from mountain biking are similar to hiking,” Pongracz said. “Both are much less severe than the impact on the trails by equestrians.”

There is also Mother Nature to consider. In a recent KCET interview, biologist Ileene Anderson of the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity – one of the parties to the original lawsuit – said the connection between roadless areas and non-threatening habitats of endangered species is obvious. She cited the classic example of the arroyo toad, whose riparian habitat is all but gone due to unrelenting development.

Erskine-Hellrigel agrees.

“Southern California chaparral is the fastest disappearing habitat in California. If we continue to let it slip away to developments, there will be nothing left. We have protected very little of this habitat, as can be seen by bear, cougar and other animals wandering into populated neighborhoods in search of food and water.

“We need the animal corridors open to guarantee them safe passage,” Erskine-Hellrigel said. “I see roadkill on a daily basis in our area, including a bear and a cougar over the last few years. If we keep this frantic pace of development, we won’t have any chaparral, nor will we have any animals to live in it. There are a lot of endangered species and rare species in these IRAs, which is reason enough to protect them.”

– – –

One of the requirements of the 2011 settlement agreement was for the Forest Service to prepare a supplemental environmental impact statement (EIS) for an amendment to the land management plans for the Angeles, Cleveland, Los Padres, and San Bernardino forests.

“The Forest Service proposes to amend the land management plans to change land use zone allocations within select inventoried roadless areas in the four Southern California National Forests,” according to its April 27 notice of intent. “The amendment also proposes to change the land management plan monitoring protocols for the four forests. This joint planning process will maintain the consistent management direction and format across the four forests. One supplemental environmental impact statement will be prepared with a Record of Decision for each land management plan.”

To help make sense of the cumbersome process and give communities a chance to weigh in, the Forest Service is conducting a series of public meetings in the ranger districts of the four national forests.

“Thus far, the Angeles National Forest has participated with the other three Southern California forests in complying with the settlement agreement,” said Seastrand. “We have assigned staff like myself to be on the interdisciplinary team.

“We have completed one key portion of the agreement by participating in a collaborative process to prioritize decommissioning of roads and trails within roadless areas,” he said. “We have reviewed the zoning of our roadless areas and defined the proposed action for the Angeles.”

Seastrand said his agency is in the scoping phase of the environmental process – defining possible alternatives to banning roads, studying the environmental effects of the ban and inviting public comment.

– – –

Within the Angeles, a bundle of hills and valleys northeast of Castaic Lake are to be combined into the recommended 40,000-acre Fish Canyon wilderness area.

“Our proposed action for the Fish Canyon and Salt Creek roadless areas, as well as a small piece of land between them, is to zone them as ‘recommended wilderness,’” Seastrand said, “and manage them according to that designation if it is adopted.”

And this is where the communities around the proposed wilderness re-zoning areas come into play: All interested environmental and recreational groups and individuals are invited to share their views on the amendments.

The public comments period closes Monday, June 11 – and every opinion counts.

“The information gathered through public scoping is used to define these alternatives based on issues the public identifies,” Seastrand said. “The legal requirement is that we provide a “reasonable range” of alternatives.

“You can think of it this way: We are required to think about and involve the public in coming up with different ways to meet the same objective, more specifically, ways that may create less impact on the environment.”

Written comments may be emailed to socal_nf_lmp_amendment@fs.fed.us or sent to: Cleveland National Forest, 10845 Rancho Bernardo Road Ste. 200, San Diego, CA 92127-2107, ATTN: LMP Amendment.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

3 Comments

Bicycles should not be allowed in any natural area. They are inanimate objects and have no rights. There is also no right to mountain bike. That was settled in federal court in 1994: http://mjvande.nfshost.com/mtb10.htm . It’s dishonest of mountain bikers to say that they don’t have access to trails closed to bikes. They have EXACTLY the same access as everyone else — ON FOOT! Why isn’t that good enough for mountain bikers? They are all capable of walking….

A favorite myth of mountain bikers is that mountain biking is no more harmful to wildlife, people, and the environment than hiking, and that science supports that view. Of course, it’s not true. To settle the matter once and for all, I read all of the research they cited, and wrote a review of the research on mountain biking impacts (see http://mjvande.nfshost.com/scb7.htm ). I found that of the seven studies they cited, (1) all were written by mountain bikers, and (2) in every case, the authors misinterpreted their own data, in order to come to the conclusion that they favored. They also studiously avoided mentioning another scientific study (Wisdom et al) which did not favor mountain biking, and came to the opposite conclusions.

Those were all experimental studies. Two other studies (by White et al and by Jeff Marion) used a survey design, which is inherently incapable of answering that question (comparing hiking with mountain biking). I only mention them because mountain bikers often cite them, but scientifically, they are worthless.

Mountain biking accelerates erosion, creates V-shaped ruts, kills small animals and plants on and next to the trail, drives wildlife and other trail users out of the area, and, worst of all, teaches kids that the rough treatment of nature is okay (it’s NOT!). What’s good about THAT?

For more information: http://mjvande.nfshost.com/mtbfaq.htm .

Mike Vandeman is a convicted criminal who has repeatedly assaulted other people on trails.

Mike is currently banned from trails in his community by a court order, as a direct result of his criminal actions.

AMEN