Have you ever looked up into an oak tree and noticed a reddish or yellowish ball that looked like an apple? Sometimes people look at this in sheer confusion. What is going on? If you look at the base of the tree, you might be able to find an old one, brown and cracked, on the ground.

Have you ever looked up into an oak tree and noticed a reddish or yellowish ball that looked like an apple? Sometimes people look at this in sheer confusion. What is going on? If you look at the base of the tree, you might be able to find an old one, brown and cracked, on the ground.

While taking children on the trail, I would tell them it was a nest.

“Look, the inside is all spongy like a sponge cake. The babies were growing up eating this.”

The idea of babies in a nest, eating their way out of sponge cake, suddenly sounded appealing and intriguing – even if I was holding an old, broken-brown gall in my hand. The power of imagination is remarkable.

Yes, that’s what this “apple” is: an oak gall.

Galls are made by many insects, but especially by one family of gall wasps, the cynipid wasp. There are many different kinds of galls. Some are small on the leaves of oak trees (they can be just 1mm in width) and are caused by the Dryocosmus minisculus. Some can be big oak apple galls caused by Andricus Californicus.

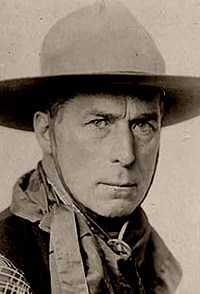

Photo: Placerita Canyon 2012 (SCVTV) | Click to enlarge

I thought I was going to write a nice little article covering what I learned about the oak gall, but the more research I did, the more complicated it became.

Many species have alternating generations. Wasps from the same species but from alternate generations look different – and when they start the process of laying an egg, it results in galls with a different appearance, too.

Let’s go back to the basics: Cynipid wasps are small, harmless, and no bigger than a fly – or even smaller. They have a short adult life, and not much is known about them, but most of their life is spent inside the oak gall, and that life cycle has been well documented.

It depends on the species and the generation, but it is usually the female that chooses the oak to lay her eggs. Each species will choose a specific part of the tree (bud, leaf, or through the bark to reach the cambium), but all use a long ovipositor to do that.

The eggs secrete various plant hormone replicas, and cause the gall to start growing. Then the oak gall produces its own vascular system, taking nutrients from the tree.

Inside the gall, nutritive cells develop and the wasp larvae feed on it. The inside looks spongy and soft, and this why it made me think about sponge cake.

Interesting little detail: The larvae keep the inside of the gall clean, and they have a distinct advantage to do that … their intestine is disconnected from their anus, so that does help a lot! The two parts of their digestive system hook up just before pupation takes place.

Cynipid wasp

The larvae can stay inside the gall for weeks or months or even years. The climate and the species will dictate when they are ready to come out. At that time, the larvae pupate into adults and make a small, round hole through the hard shell of the gall to escape from the nest.

If you find a gall on the ground, look carefully for the hole. You will usually find it, and seeing how small it is, you will have a better understanding of the size of the cynipid wasp.

The outside of the gall is hard like a shell, but it is a thin layer that you can crack with your hands. It does look like a perfect nest: soft inside, hard on the outside. The gall provides nutritious food and also protects the larva from parasites and predators.

The gall color depends on the season, the amount of exposure to the sun, and how new the gall is. It can turn a bright shade of orange and look really pretty in the sun.

Galls do not cause serious damage to the oak tree, but an unusually large number of galls could reduce the vitality of the oak.

There are many more interesting details about the cynipid wasp, and most have to do with their sexual adaptation. During one generation, they have the regular male and female mating, and the female will lay the eggs; the next generation is asexual. That means the female wasp will have an offspring while no male action is needed. That is called parthenogenesis. It is quite complex, but if you want to learn more about this little insect, you can always do your own research.

I discovered one thing long ago that if somebody covers the basics with you, you will know if the topic attracts your curiosity, and that opens the door to more and more research.

The more you learn, the more you realize how much you don’t know, and it gets even more interesting with each discovery.

Have a great week.

Evelyne Vandersande has been a docent at Placerita Canyon Nature Center for 27 years. She lives in Newhall.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.