Palladino worked on more than a dozen of Frank Sinatra’s Capitol albums from 1953-1962. Photo: Stephen K. Peeples/stephenkpeeples.com

Longtime Friendly Valley resident John Palladino, a pioneering Hollywood sound engineer turned Capitol Records producer/artists & repertoire exec whose sonic fingerprints are on millions of records released worldwide, died at home Dec. 20, surrounded by members of his immediate and extended family. He was 94.

Palladino had suffered head injuries and a fractured neck vertebra in a bad fall on Dec. 7 and did not recover, according to former daughter-in-law Barbara Blanchard, now a resident of Missoula, Montana. He was hospitalized until Dec. 18, when he desired to return home, she said.

In Palladino’s 40-plus year studio career, which spanned the schlock era to the rock era and included more than 30 years as a staff engineer-producer at Capitol Records from 1949-1982, he engineered, mixed, produced and/or edited recordings by artists in a wide variety of genres.

From Sinatra to The Beatles to Steve Miller

Most notable are classic recordings by jazz legends such as Kid Ory, Nat “King” Cole, Frank Sinatra and Stan Kenton to gold and platinum hits by rock superstars including the Steve Miller Band, Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Band, Pink Floyd, Paul McCartney, The Beatles and more.

Along the way, Palladino worked with recording technology from the ancient wax discs and direct-to-disc mono acetates of the 1930s-‘40s to the magnetic tape of the late ‘40s and stereo multi-tracking of the late ‘50s-late ‘70s, all the way to the bleeding-edge early digital technology of the late ‘70s-early ‘80s.

In particular, continuing to experiment at Capitol as he had at LACC, Palladino developed methods of multi-miking and close-miking that brought the usually hard-to-hear rhythm section right into the bottom of the mix, where it belonged. He filled out the sound, and made it round.

But beyond his many professional accomplishments, sung and unsung, Palladino most enjoyed his family and his faith as a devout Catholic. Before he died, he was patriarch to five generations with a sixth on the way. They revered him even more than his professional colleagues, as a husband, father, uncle, grandfather and great-grandfather.

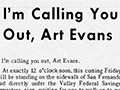

As an engineer-producer, Palladino was probably best-known and most widely respected for his work with Sinatra, who recorded 19 albums for Capitol from 1953-1962.

Before the National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences began awarding Grammys in 1959, NARAS awarded Palladino a special recognition for his engineering work on The Voice’s third Capitol LP, 1955’s “In the Wee Small Hours,” a set of melancholy ballads with sparse arrangements by Nelson Riddle.

John Palladino, top, and Val Valentine were engineers at Radio Recorders in Hollywood in the 1940s. Photo: Courtesy Palladino-Blanchard Family.

They Called Him ‘Mr. Snips’

In addition to his sound production expertise, Palladino earned a rep as an ace tape editor, shortening album tracks for what would become hit singles, like Paul McCartney’s gold chart-toppers “Band on the Run” (1974) and “Silly Love Songs” (1976), and Little River Band’s “It’s A Long Way There” (Top 30, 1976) and removing profanity for AM radio play, as in editing the second half of the word “bulls**t” from the single version of Pink Floyd’s “Money” (No. 13, 1973).

Palladino was so good that his single edit of “Band on the Run” hit No. 1 before anyone really realized it was shorter. He picked the best parts. McCartney was not asked for permission ahead of time, which was a huge gamble by label brass. But it was no big deal to Mr. Snips.

“I was up in San Francisco, producing Joy of Cooking,” Palladino said in a series of summer 2010 interviews with this reporter. “[Capitol] sent [the album track] up to me, I made the edit, and sent it back.” And continued producing his band.

At some point after “Band on the Run” topped the charts, Palladino and McCartney met at a label event, and had a nice chat. “But he never said anything about [the sneaky edit],” Palladino said.

He also edited tracks on Capitol’s U.S. version of “Beatles Rarities” (No. 21, gold, 1980) and “The Beatles’ Movie Medley” from Capitol’s “Reel Music” album (No. 19, gold, 1982), as well as “The Beach Boys Medley” (No. 12 single, 1981).

That’s all just for starters. There were so many other stories about edit jobs for so many artists, all the time.

“I just did whatever [the Capitol A&R and promotion execs] threw at me,” Palladino said. “Other labels would ask me to edit their tracks, too.

“And I never used a jig to line up the splices – I did it free-hand,” he said.

Awe-struck by Palladino’s superior editing skills, his Capitol colleagues in the ‘70s were the ones who nicknamed him “Mr. Snips” because of his superior editing skills – and the pair of editing scissors with the points taped up that he carried in his back pocket, so they’d always be handy.

“To me, anyone in the music business when I started was very fortunate,” Palladino said in 2010, looking back at his 40+ years in the studios.

“That kind of career, and being in that environment – it was like, ‘How can I enjoy my work so much and still get paid for it?’” he said. “There is no better job in the world than one where you can make music and get paid.”

John Palladino (right) and former Capitol colleague Stephen K. Peeples hit the roof of the Capitol Tower on a visit on August 10, 2010. Photo: Greg Parkin.

Palladino’s Lasting Influence

John Palladino and his studio techniques have been a significant influence on many other young engineers coming up in the sound recording industry. In October 2010, at age 90, he was invited to return to Capitol Studios, which he did for the first time since 1982, to be interviewed for an ongoing audio history project.

He was surrounded by more than a dozen other audio engineering nerds, from senior engineers to a couple lucky interns in their early 20s who had yet to cut tape – even with an editing jig.

“Our engineers today revere him,” said Greg Parkin, who handled special events for the studios, as he and this reporter observed the roundtable scene from the Studio B control room.

The studio crew spent two and a half hours asking the Palladino about working with this artist or that, how technology had evolved, and some of the tricks he used in miking certain vocalists or instruments.

Among the guest panelists was Al Schmitt, who today with 23 Grammy awards and recognitions is the most honored sound recording engineer in history. His most recent project, Bob Dylan’s “Shadows in the Night” album of songs associated with Frank Sinatra’s early career, is due Feb. 3 from Sony.

“John’s always been an inspiration to me,” Schmitt told this reporter in 2010. “Some of the records he did with Stan Kenton and Sinatra have just been things I’ve admired all my life and strived to copy. The way [Palladino] balances was so great. He’s just such a musical engineer.”

Schmitt recalled an example: “That trombone solo by Milt Bernhart on Sinatra’s ‘I Got You Under My Skin’ – just magic, and just so, again, musical. It’s not just somebody who has the technique; it’s also someone who had the musicality, because John was an arranger, too. I think the world of him.”

During the roundtable, when the studio guys cued up classic tracks he’d worked on and played them back for his comments. Unfortunately, he couldn’t hear them well.

“Producing the rock bands ruined my ears,” he said, particularly fingering Quicksilver Messenger Service, and that his blown-out hearing factored into his decision to retire early.

Early Days – College Radio, Army Air Force, Radio Recorders

John Palladino was born March 29, 1920, in Ashley, Pennsylvania, to Tony Palladino, a carpenter, and Tony’s wife Lena, a full-time mother.

John was 2 years old when his parents moved their young family to Southern California. Eventually, he had four siblings.

“The family was always music-oriented,” he told this reporter in 2010. “In those days you had to entertain yourself, and usually it was about sitting down to a piano or picking up a guitar. So I was always next to music and always liked music, but I’ve never felt like I was a student of music. As an Italian, I was just supposed to be able to appreciate music.”

He picked up the accordion in high school. “That formed a good background for what I got into later, when I was an arranger, then in a band at Los Angeles City College,” he said.

Palladino actually went to LACC to study architecture. But after discovering LACC’s tiny radio station also had a recording studio, he put it to good use right away.

“We could draw talent in there and make the arrangements and record them and listen back to them,” he said. “That’s how I learned — just by practical hands-on stuff.”

After service in the Army Air Force from 1940-1942 (where he was an arranger and then a radio operator) and an honorable medical discharge (rheumatic fever), he returned to L.A. and went right to work in Hollywood studios.

“They welcomed me with open arms,” he said.

“When he was discharged, he received some disability pay, but wrote the [government] a letter when he found a job and told them he didn’t need any more disability pay since he was able to work,” Barbara Blanchard said. “Imagine that….who does that these days?”

Palladino’s first major Hollywood studio job was at Radio Recorders, which specialized in pressing transcription discs of radio shows.

“Radio Recorders was also unique place because it was the start of a transition from wax discs…to 16” acetates.” Palladino said. “They were excellent recording facilities. They went to all the best people at the time. They had custom lathes, they got the best recording heads, the best microphones, and they were gung-ho on getting the best sound they could.”

Palladino and his sister Rose were both working at Radio Recorders in the late ‘40s, when he met fellow engineer Evelyn Blanchard, one of Rose’s co-workers.

At the time, Blanchard was divorced and had a son, Hal, born in 1937. Palladino and Blanchard fell in love and eventually married on Jan. 6, 1951, John raised Hal as his own son, and he and Evelyn were happily married for 48 years, until she died in 1999.

After wax and acetate discs, the next recording breakthrough, magnetic tape recording, was not far behind. Soon after World War II ended in 1945, Les Paul began experimenting with multi-tracking on a prototype reel-to-reel machine confiscated from the Nazis. (It was a gift from Bing Crosby, Paul told this writer in 1991.) Soon the studios were all going to tape.

Multi-tracking on tape, introduction of 45 rpm singles and 33 rpm albums, and stereo were among the big-deal recording milestones of the 1950s, and Palladino was in the thick of those developments as well.

“With tape, you could actually cut it,” Palladino said.

So began the legend of Mr. Snips.

Capitol Studios, Nat “King” Cole and Frank Sinatra

Capitol Records, founded in April 1942 by Johnny Mercer, Glenn Wallich and Buddy DeSylva, opened its first recording facility in 1949.

Not long after meeting his future wife at Radio Recorders in ‘49, Palladino segued to a staff engineer position at the new Capitol Studios, in the former KHJ Radio building on Melrose Avenue, next door to the Paramount Studios lot.

In this era before album liner notes listed production credits and Grammys were handed out publicly, Palladino soon earned a reputation among his peers, if not the general public, for his quality work behind the board with Capitol artists like Cole, Dean Martin and especially Sinatra. They, along with Les Paul & Mary Ford, were among the label’s first million-selling superstars in the early ‘50s and into the early ‘60s.

Palladino served as the mixing engineer for all of Cole’s small-combo mono sessions for the label, as well as most of Sinatra’s early Capitol sessions with larger orchestras, at Capitol’s Melrose studios, then at the new Capitol Studios in the Tower on Vine Street when the building opened in spring 1956. Palladino learned to make particular use of the unique new natural echo chambers built under the studio’s parking lot.

With studio staffers Voyle Gilmore or Dave Cavanaugh producing, Palladino engineered and/or mixed most of the 19 albums Sinatra recorded at Capitol’s two studios from 1953-1962, according to Charles L. Granata’s essential “Sessions with Sinatra: Frank Sinatra and the Art of Recording” (A Cappella Books/Chicago Review Press, 1999).

“The Voice” had a reputation for being tough on musicians and studio crews during sessions.

“[Sinatra] was always so much a perfectionist – I could never fault him for that,” Palladino said. “If a guy is that good and you have to suffer a bit, you have to go along with it.”

Palladino and Sinatra Shake Down New Capitol Studios

Palladino engineered then mixed the first of Sinatra’s mono sessions at Capitol’s new Vine Street studios.

In fact, Palladino engineered and mixed the very first sessions at the new Capitol Studios – and coincidentally with Sinatra.

They recorded the album “Tone Poems of Color” in Studio B, the smaller of the new studio’s three rooms but the first fully operational, with Sinatra calling the shots as producer.

“He conducted a large orchestra, about 60 pieces jammed in the room, recording things by different arrangers,” Palladino said.

He added he and Sinatra weren’t very happy with the sound in Studio B, but Palladino corrected the problems when he mixed the master tapes for release.

After that initial shakedown, and completion of Capitol Studios’ large Studio A and a smaller production room dubbed Studio C, Palladino said it took the designers and engineers a couple years of modifications and experimentations to get the rooms right. But from the late ‘50s on, Capitol has been one of Hollywood’s best-sounding and most in-demand studios.

Steve Miller, The Band, Quicksilver

In the late 1960s, as Capitol was trying to catch up with the hippie counterculture by signing young artists and groups, label execs signed artists like Steve Miller, Joy of Cooking, and Quicksilver Messenger Service from San Francisco and The Band from New York, then put Palladino in charge of A&R and production for this new breed.

Over the next decade and a half, Palladino also produced Capitol albums by The Sons of Champlin, Juice Newton, Jackie DeShannon, Caldera and Bloodrock, among many others.

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) has honored Palladino with numerous gold, platinum and multi-platinum record awards, among them “The Band” by The Band (1969) and four albums by The Steve Miller Band – “The Joker” (1973); “Fly Like an Eagle” (1976); “Book of Dreams” (1977) and “Abracadabra” (1982).

Steve Miller – ‘Somebody Give Me a Palladino!’

None of the aforementioned gazillion-selling Miller albums would likely have happened – at least not on Capitol – without John Palladino, a consummate diplomat among everything else.

Miller, who as a child was a protégé of Les Paul, was the first long-haired San Francisco-based artist Capitol signed in 1967, and immediately ran into the Establishment’s brick wall.

Miller remembers how he was ready to bail after Day 1 when Palladino came to his rescue, and recalls their very last session together on the day the engineer retired in 1982 – 15 years and those aforementioned gold and multi-platinum albums later:

“John was my first working contact at Capitol Records on the first day I showed up to discuss recording my first album after I had signed my contract,” Miller said in an email.

“The year was 1967,” he said. “He had a short haircut, a Navy blue jacket and a necktie and he was my A&R executive rep for the company. My hair was very long and I was from San Francisco. We were really different from anyone he had worked with before. It was a classic meeting of the old and the new.

“I was very excited to get started and thought I would be getting a lot of help from my new mentors,” Miller said. “It turned out I was walking into a political can of ambition. The engineering staff hated each other and anyone from San Francisco. Everyone was trying to move up in the department and get rich quick. Every one of the newly signed bands was fighting for resources and the junior A&R staff at Capitol was trying to steal the best bands and manage them. They wanted your publishing and to cut your tracks with their own pals. It was a quick education.

“I tried to record at Capitol but the engineering staff wouldn’t book my sessions until midnight. They didn’t want me to be seen at the Tower,” he said.

“The first night we set up starting at midnight and finally began recording at 4 a.m. I had to stop an hour later. I was sound asleep,” Miller said.

“The next night they made us move all our set-up gear to a different studio, re-set it and re-tune in the drums, and as soon as we were ready to go the entire engineering staff walked out. They just disappeared,” he said.

“It was a horrible thing to do to a young artist on his first sessions,” Miller said. “I was broke, inexperienced and this was my first set of sessions for Capitol. They completely humiliated me and wasted my resources and time. I had brought all my gear and the band from San Francisco and was staying in a hotel with 10 people on the tab.

“John was the first guy I called at 4 a.m. I offered to return the newly signed contract I had just spent nine months negotiating with three major labels for,” he said. “I couldn’t get out of my newly signed contract. The guy who signed me, Allen Livingston [label president at the time] was then fired.

“John was amazing. He was the guy assigned to bring me back into the fold,” Miller said. “He was a total gentleman. He calmed me down and offered to help me find a better studio. I ended up going to London to record at Olympic Studios [with Glyn Johns]. John and I eventually became good friends and worked on many projects together.

“John had a complicated position,” Miller said. “He needed his job and he had to take care of a lot of egos who were fighting each other to run the company, people who were careless and dangerous for [an artist’s] career.

“At the same time, he had to keep the artists in line. So he was the man in the middle who kept the whole company all together — without threatening anyone’s position,” he said. “He really needed to keep his job and he didn’t take sides and seemed like the only sane person in the company. It was quite a lesson in corporate politics.

“The entire time we worked together, from 1967 through 1982, he never mentioned his early work with Sinatra or shared his history with me so I didn’t even know about that part of his life,” Miller said. “I wish I had. I was always trying to pull him over to my side, but he always remained neutral. You couldn’t tell if he liked your work or not.

“John did his job well and outlasted a lot of ‘would-be’ presidents [and a few real ones] at Capitol before he retired,” he said. “On his last day at Capitol he was sound asleep in the control room as we were finishing the mix of ‘Abracadabra,’ which became my third No. 1 single. He went out with a bang as the executive producer on a worldwide No. 1 hit.

“In truth he was glad to be leaving and moving to Bear Lake at the age of 62, relatively early in life, to enjoy his family,” Miller said. “He had had an amazingly creative and rewarding early career working with Sinatra, worked his way up the ladder only to see the entire culture change with The Beatles, and ended up working in a recording company that was at war with itself and its own artists.

“In the end it was clear he paid his dues and wanted to get out of there. He was the one sane voice at Capitol records for years, and when he left things really fell apart quickly,” her said.

“He was a good and wise man who survived and thrived in a very difficult situation and help everyone he worked with.”

Palladinos Move to Friendly Valley

John and Evelyn Palladino moved from L.A. to Newhall in 1970, and into the Friendly Valley development before it became dedicated to seniors. Between his sessions at Capitol, and after he retired, he was active in the community.

“I joined the Friendly Valley Association No. 5 board in 1985-1986, and have remained on and off [the board] as the years have gone by,” Palladino said in 2010. “I still serve in an advisory capacity.”

The Palladinos did endure the hardship of a couple miscarriages over the years, and their son/stepson Hal Blanchard’s sudden death of renal cell cancer in 1986, at age 49.

Hal had married Barbara Boxhorn in 1960 and they had four children before divorcing amicably in 1977. Hal remarried in 1981, to Linda Hein, so John Palladino actually had two daughters-in-law.

“After Hal’s death, Linda and I remained close friends and collaborated on raising the four children,” Barbara Blanchard said. “Both Linda and I also stayed close to John as his ‘daughters’ and shared duties to make sure John could still live independently.”

Palladino’s Final Days

Palladino lived by himself with family support in the years after his wife’s death in 1999. He was in relatively good health until October 2013, when he suffered a fall. Barbara, Linda and other family members helped him regain his health, but from that point he slowly began to fail, Barbara said.

On Dec. 7, 2014, a Sunday, Palladino drove by himself to the 11 a.m. Mass at St. Clare of Assisi Catholic Church in Canyon Country, where he was a longtime parishioner and volunteer.

“John always dedicated a Mass in Hal’s memory on Dec. 7, so I’m sure that is one reason for his determination to drive himself to church,” Barbara said.

After Mass, Palladino had just finished lunch and was walking to his car in the restaurant parking lot when he took the final fall. Others rushed to his aid and he was immediately hospitalized. By Dec. 18, though, he was still not recovering, and desired to go back to Friendly Valley, Barbara said.

At home, Palladino was in hospice care as many family members visited. He was surrounded by immediate and extended family when he died two days later on Saturday, Dec. 20, at 5:56 p.m. Barbara said.

St. Clare’s held a funeral Mass for Palladino Dec. 30, and he was interred at the San Fernando Mission cemetery, next to wife Evelyn and stepson Hal.

Palladino was also preceded in death by his father and mother, Tony and Lena Palladino; his brother, Michael Palladino, a B-24 pilot killed in World War II; and his sister, Rose Borden, also a sound engineer, who died in 2013.

Palladino is survived by his sister Marie Romaine; his brother Anthony Palladino (wife, Ginger); and daughters-in-law Linda Blanchard and Barbara Blanchard. Barbara is mother of the four Blanchard grandchildren – Cynthia, Jennifer, John and Michelle.

Palladino is also survived by 11 great-grandchildren and a great-great-granddaughter, as well as niece Susan Palladino and six nephews – Daniel and Michael Palladino, Bill and Michael Borden, and James and Paul Romaine.

Family Tributes – Palladino’s ‘Magical Invisible Hand’

Barbara Blanchard has many fond memories of her former father-in-law, including his interest in motorized model airplanes, crystal and stained glass art, fishing, and building things: Palladino built two cabins, one in Green Valley and the other in Big Bear. His glass artwork still graces many homes and doorways in Friendly Valley.

“He loved taking the grandchildren fishing on his boat in Big Bear Lake,” she said. “He taught ‘Little John’ all his skills of construction, bricklaying and handyman work. In fact, a lady in the Friendly Valley office last month asked me where his grandson was. She remembered them doing all sorts of projects together and John bringing ‘Little John’ along.

“He built a whole wing onto our house in Solvang,” Blanchard said. “He and I crawled into the long attic and put down new insulation. We often laughed at the two of us squeezed into the crawl space, working with that horribly itchy stuff.”

“My grandpa was the smartest man in the world. He knew everything and he could make anything,” Cynthia Blanchard, eldest of Palladino’s grandchildren, said in a separate email.

“I spent many days with him at the studios, both here and in San Francisco,” she said. “He and my grandmother took me with them to the Grammys as well.

“My grandpa worked from home sometimes and I remember sitting on the floor in his editing room watching him manually turn the reel-to-reel until he somehow heard just the right spot,” Cynthia said. “He would then splice the tape, do the same thing again and splice it back together. It all sounded like jarble to me and to this day I can’t figure out how he did it.

“I spent most of my childhood years with my grandmother and grandfather as my mother was working my father through school,” she said. “I spent months with them up in Big Bear living in a trailer on the property while my grandfather built their A-frame cabin by hand. I would follow him around like a shadow.

“The most memorable times of my life were the times I spent with him and my grandmother growing up,” Cynthia said. “My mother told me he had said his happiest moments were at the cabin, too. Oh, the memories – him reading me my favorite book, ‘The Pokey Little Puppy,’ teaching me how to drive his Sportomatic Porsche 911T, fishing in Big Bear Lake…the list goes on and on.

“My grandfather was a very, very patient man,” she said. “My grandmother [Evelyn] was a very outspoken woman and he loved her dearly…They were so funny. Now, this may be a little personal, but it shows the kind of man my grandpa was and the love he had for my grandma. When she was failing, I stayed with them for a week. In the middle of the night I was awakened by the sound of a motor running. I got up and went to their bedroom and there he was with the blow dryer, warming the commode seat so it wouldn’t be cold when my grandmother sat down. Now, that’s love and devotion!!

“I have always thought my grandfather was a saint,” Cynthia said. “In my 53 years of life with him, I never heard him swear, raise his voice or have a negative thing to say about anyone. He is my HERO! The love, pride and respect I have for him is immeasurable. The loss I feel is so incredibly painful, I truly think a part of me went with him when he passed.”

“John was humble – maybe too humble,” said Daniel Palladino, son of his youngest brother Anthony Palladino, and a former writer on the long-running “Roseanne” TV series.

“The combination of John’s natural musical skills and completely unflappable nature made him the perfect engineer to work with,” Daniel said. “Sinatra’s people loved him, which means John never pissed off Sinatra, and that was probably a rare feat. John was the magical invisible hand that helped create Capitol Records.”

Online Palladino Tributes

Family, friends and former colleagues have contributed numerous tributes to a John Palladino memorial website set up by Cynthia Blanchard.

Among the initial posts are by Robbie Robertson of The Band; former Capitol engineer David Cole; former Capitol A&R execs Bruce Garfield, Bruce Ravid and Richard Landis; former Capitol President Don Zimmerman; and former Capitol Chairman Bhaskar Menon.

Daniel’s brother Michael Palladino has created a John Palladino memorial Facebook page.

The Steve Hoffman Forum thread about Palladino includes more tributes from recording industry professionals.

Santa Clarita journalist Stephen K. Peeples was Capitol Records’ Editorial Director and worked with John Palladino at the Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood from 1977-1980. He would like to thank the Palladino-Blanchard family, Steve Miller, Al Schmitt, Martin Melucci, Chuck Granata and Paula Salvatore for their invaluable assistance with this story.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

2 Comments

RIP John

I didn’t know John . . . but I was very impressed with his accomplishments and I do know Gloria from Friendly Valley, where I also live.