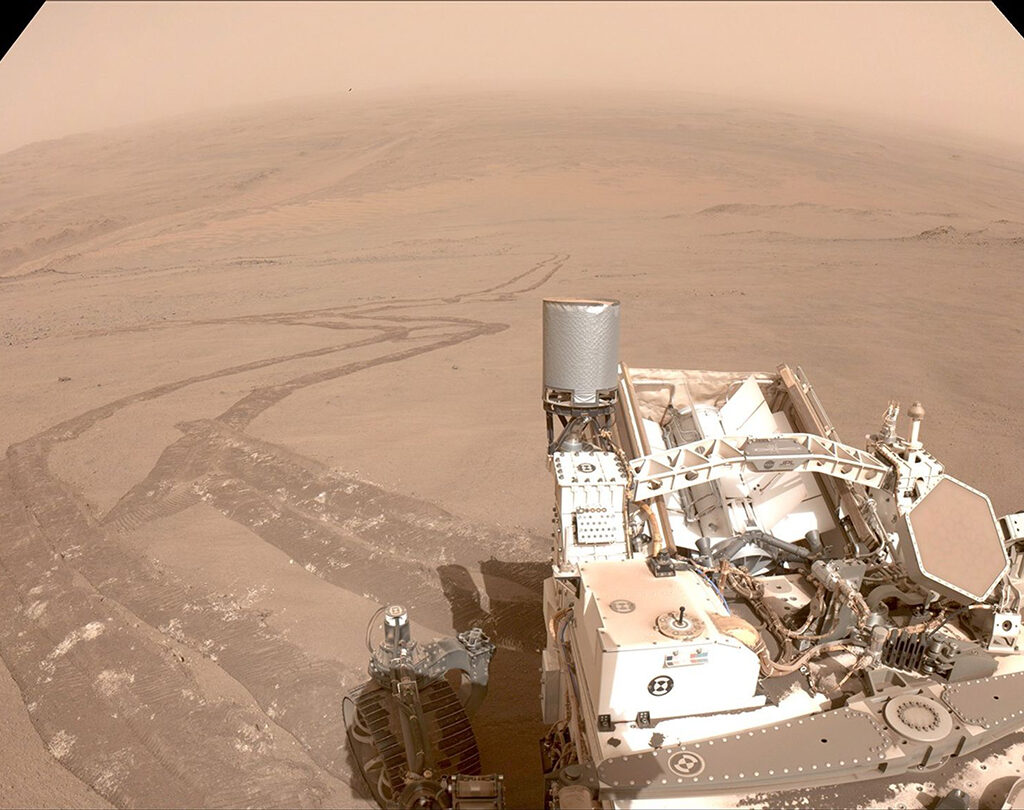

It may still be a few years off, but California State University, Northridge biology professor Rachel Mackelprang is part of a team of scientists who are developing safety protocols for when samples collected from the martian surface by NASA’s Perseverance rover or other missions are brought to Earth.

The goal is to ensure that the samples of rock, soil and dust, do not contain Martian microbial life that could jeopardize life on Earth. If life is found in returned samples, they would need to remain in a high containment facility or be sterilized. The first of four articles outlining the team’s recommended protocols, “The Abiotic Background as a Central Component of a Sample Safety Assessment Protocol for Sample Return,” was published earlier this year in the journal Astrobiology.

Mackelprang, who runs a research lab and teaches in the CSUN College in Science and Mathematics, said the first article focuses on establishing an “abiotic baseline.”

“We don’t expect there to be modern extant life in returned samples because the environment on the Martian surface is not conducive to the survival of life. However, we need to verify that there isn’t life in those samples, in part because they could potentially pose a hazard to the Earth’s biosphere,” she said.

Mackelprang said that most people do not realize that the Earth is microbial.

“Microbes exist in every environment,” she said. “They power geochemical cycles. For example, when plants die, or anything dies, microbes degrade and recycle the remains, returning the components to the environment. So, the idea of an invasive species from Mars is something, even though it’s a low probability, that we should take seriously.”

Joining Mackelprang as co-authors of the paper were Bronwyn L. Teece, and David W. Beaty, who are with NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and California Institute of Technology; Heather V. Graham with the Solar System Exploration Division of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center; Gerald McDonnell with Microbiological Quality & Sterility Assurance; Barbara Sherwood Lollar with the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Toronto; Sandra Siljeström with the Department of Methodology, Textiles and Medical Technology with the RISE Research Institutes of Sweden; Andrew Steele with the Carnegie Institute for Science, Earth and Plants Laboratory in Washington D.C., and the Sample Safety Assessment Protocol Tiger Team.

Mackelprang and her colleagues noted that 3 to 4 billion years ago, as life was forming on Earth, Mars was likely more habitable than it is today, with a thicker atmosphere and liquid water at the surface. The discovery of a past atmosphere and water has led to the hypothesis that Mars could have hosted life in its ancient past, and signs of this life could be found in the samples the Mars Perseverance rover has collected. The rover was sent to Jezero Crater, which hosts an ancient delta that may contain evidence of past microbial life.

Just in case life arose on Mars and is still viable, the samples are mandated to be kept in a high containment facility until they are determined safe to be released for broader analysis “if they meet a threshold of acceptable risk,” Mackelprang said.

“We can never say with 100 percent certainty that there is not a potential hazard,” she said. “But we can establish a threshold, say a one in a million chance, or maybe a one in a billion chance, that life is present.”

Though it could be a decade or more before the Mars samples are brought to Earth, Mackelprang said it is important to develop plans for safety now, to ensure that when samples finally arrive procedures are in place.

“The proposed sample safety assessment protocols were developed with the flexibility to incorporate scientific and technological advances between now and when samples are eventually returned,” Mackelprang said. “Successful application of the protocols would require further research and development, which includes a continued focus on developing of state-of-the-art methods and technology for use on martian samples.”

She noted that the United States may not be the lead country that eventually brings the samples to Earth.

“It could be China, Russia or some other country,” she said. “We developed protocols that could be applied regardless of who brings samples to Earth.”

The team’s first recommendation of establishing an abiotic baseline would “enable us to detect signatures of life and provide a framework for conducting a safety assessment,” Mackelprang said. She and her colleagues estimate the proposed safety assessment would consume less than 10 percent of the returned material.

That baseline is just the start, Mackelprang said. She and her colleagues are planning to release three more papers outlining components of the protocol to mitigate any danger that might arise as researchers explore what they can learn about Mars, our solar system and the universe from the Martian samples.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.