A re-examination by CSUN anthropologist Hélène Rougier of bones first excavated in the cave site Ilsenhöhle beneath the castle of Ranis, Germany by archaeologists in the 1930s has contributed to the discovery that modern humans reached northwest Europe more than 45,000 years ago, thousands of years before Neanderthals disappeared.The cave site Ilsenhöhle beneath the castle of Ranis. Photo © Tim Schüler TLDA, License: CC-BY-ND 4.0.

A re-examination by California State University, Northridge anthropologist Hélène Rougier of bones first excavated by archaeologists in Germany in the 1930s has contributed to the discovery that modern humans reached northwest Europe more than 45,000 years ago, thousands of years before Neanderthals disappeared.

Rougier is part of an international team of researchers who have been able to document the earliest known Homo sapiens, or modern humans, fossils in central and northwest Europe. Their research reveals for the first time that those fossils were accompanied by markers — namely long blades made into points — for the Upper Paleolithic era known as Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician, which existed more than 45,0000 years ago.

Those same markers have been discovered at locations across Europe, from Moravia and eastern Poland to the British Isles, and can now be linked to an early arrival of small groups of modern humans in northwest Europe, several thousand years before Neanderthals disappeared in southwest Europe.

“Early modern humans were much more advanced than we typically give them credit for,” Rougier said, noting the discovery that Homo sapiens traveled as far as Germany in small groups indicates that they were sophisticated enough to be curious about what was beyond their usual territory and left the comfort of their “home” to see what was “out there.”

“We tend to think of them as ‘cavemen,’ primitive,” Rougier said. “Yet, they used natural features, such as the overhang of a cave, to get protection from the elements; they lived in organized groups; and they understood their environment enough to get the foods they needed. They were sophisticated enough to choose some things over others, and they passed on tradition, like making tools in a certain way. So, yeah, they were a little more complex than we give them credit for.”

The results of the researchers’ discovery were recently published in three articles: “Homo sapiens reached the higher latitudes of Europe by 45,000 years ago,” in the journal Nature and “The ecology, subsistence and diet of ~45,000-year-old Homo sapiens at Ilsenhöhle in Ranis, Germany” and “Stable isotopes show Homo sapiens dispersed into cold steppes ~45,000 years ago at Ilsenhöhle in Ranis, Germany” in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Rougier, who teaches in CSUN’s College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, is one of 125 researchers from around the world working together for more than a decade to explore prehistoric life in Europe, hoping to gain perspective on what human life was like before recorded history. Their disciplines span the spectrum, from biological anthropology and archaeology to biochemistry and genetics. The interdisciplinary approach provides an opportunity to bring new perspectives and raise questions that individuals in a particular specialty may not consider or be able to resolve.

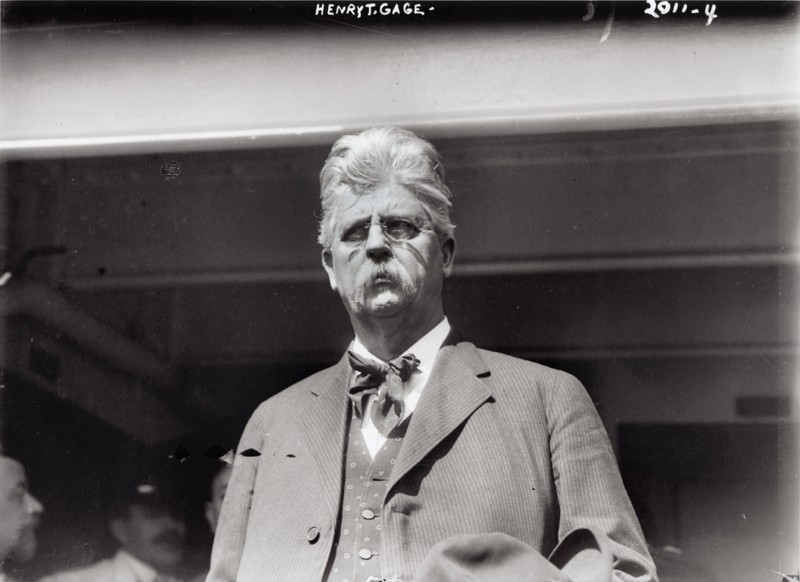

The team’s latest efforts involve the cave Ilsenhöhle, located beneath the castle of Ranis in Germany. The researchers re-excavated the Ranis site to locate the remains of an earlier excavation that took place in the 1930s. They also wanted to clarify the stratigraphy and chronology of the site and to identify the makers of the LRJ points.

“One of the things that made this site so interesting in the first place was the fact that when it was first excavated, tools (the blades made into points as well as some finely made leaf points) were found,” Rougier said. “People didn’t really know how to characterize them. They didn’t know if it was the late Neanderthals who made them, or our early ancestors who arrived in Europe. Lots of people in different places in Europe have been trying to figure out who made those things. We were trying to figure out the answers to their questions.”

When Rougier’s colleagues got to the bottom of the original excavation, more than 26 feet below the surface, they found about five-and-a-half feet of rock their predecessors could not get past. After carefully removing the rock by hand, they found the LRJ layer and thousands of fragmented bones, including pieces that belonged to modern humans.

Rougier led a new analysis of bone fragments originally collected in the 1930s. Each fragment was examined individually in an effort to identify human remains.

Once 13 human skeletal remains from both the old and new excavations were identified, DNA was extracted and analyzed. Researchers were able to confirm that the fragments belonged to Homo sapiens. They also found that some of the fragments from both excavations belonged to the same individual or were maternal relatives.

“We were able to get DNA from the bones — we only have part of the DNA for now and are working on the rest — but there is one bone from the new excavation that has the same mitochondrial DNA as several of the bones originally found in the 1930s,” Rougier said. “It clearly shows the connection between the old and new excavations, and that those modern humans, with at least one person who was closely related to another, visited the cave on different occasions.”

By using radiocarbon dating, the researchers discovered that Homo sapiens sporadically occupied the cave as early as 47,500 years ago, thousands of years before Neanderthals disappeared from Europe.

An analysis of the stable isotopes of animal teeth and bones found alongside the human fragments offered insight into the climate conditions and environments that the pioneering groups of Homo sapiens encountered around Ranis. Those early modern humans had to deal with a very cold continental climate and open, unforested, grassy landscape, similar to what is found in Siberia or northern Scandinavia today.

“We’ve been able to show that our ancestors were really like explorers — they were mobile, they adapted to their environment, and they moved when the climate changed,” Rougier said. “We have to understand that when these Homo sapiens ancestors visited north central Europe, it was a very cold environment. They were originally from southern Europe, where the temperatures were much warmer, and the environment was much more hospitable. Yet, they still made the trip.

“As we examine those movements, I think it’s important to reflect on the fact that climate has always affected us,” she said. “Today, we’re trying to counter some of its impact using our technology, but we are still animals in the natural world — though, we’re advanced, technological animals. Climate is still around us and we are still dependent on nature. I think what we’ve learned so far about early modern humans can put things into perspective.”

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

0 Comments

You can be the first one to leave a comment.