LOS ANGELES — The abbreviated history of COVID-19 in Los Angeles County began with a head start and ended with a game of catch-up to vaccinate 10 million residents.

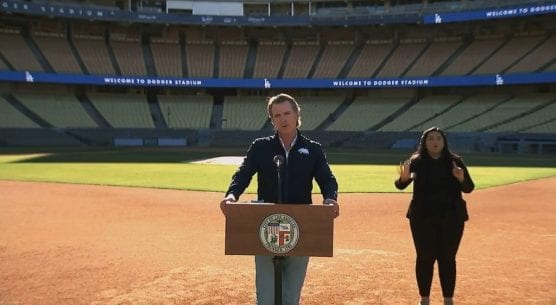

After several months of bending the curve of new infections in early 2020, L.A. became the nation’s epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. As 2021 dawned, the county’s massive testing system gradually shifted its focus — like turning a giant ship — to vaccination for health care workers and seniors 65 and older.

In record time, large-scale immunization sites went up to meet the new demand to vaccinate as residents hoped the vaccine heralded the final phase of the yearlong turmoil. But federal bottlenecks and local mismanagement have tripped up the vaccination process.

“We’re definitely seeing progress, which is to say we’re nowhere near where we need to be,” said Dr. Shira Shafir, associate professor of community health sciences and epidemiology at UCLA. “There is optimism that the pace of vaccinations is speeding up. The Biden administration will give a three-week visibility on vaccine availability instead of one week and additional steps are being made. But we have to balance that optimism with a healthy dose of realism.”

So far, L.A. County has received around 800,000 vaccine doses for its 10 million residents. Along with five mega vaccination sites, people can be inoculated at more than 150 other locations along with pharmacies, community clinics, and health centers. But vaccinations are being administered in a slow drip due to a global shortage that has frustrated many.

“Getting the vaccine to all residents who want it — regardless of income, immigration status, or transportation mode — is a high priority and something we are working urgently to address,” an L.A. County Emergency Operations spokesperson said. “We deeply apologize for any inconvenience and we are grateful for the public’s patience as we ramp up to meet the need.”

Like many things during the pandemic, much of that inconvenience and frustration to vaccinate starts online. Most vaccination appointments must be made on the internet in short windows, and securing a slot has taken on the frenzy of trying to win concert tickets from a radio show.

On Thursday, county health officials said 25,000 appointments to vaccinate were available. They filled up in two hours.

This week, resident Candice Kim managed to snag two appointments for elderly neighbors who do not speak English after securing appointments for her parents.

Kim, a health education specialist and project director with a group aimed at transforming the global trade system, acknowledges she’s able to secure vaccination slots because she’s working from home during the pandemic. Slots open up with little notice online and Kim nabbed two for her neighbors. Unfortunately, appointments were at two locations on two different days and her neighbors lacked the strength to go to both locations in the same week.

Still, Kim remains on a mission to help as many seniors until more vaccines become available.

“I’m going to keep adopting a new, non-English speaking, non-internet connected 65 and older to find appointments for until we get them all done,” Kim said. “I feel like we should all be in an emergency mobilization to help seniors over the digital divide so they can get appointments.”

The digital hoops to get an appointment can seem daunting, especially for seniors who may not understand what an SMS alert is or how to monitor the online activities of a health agency.

Kim set a text message alert for the county Department of Public Health Twitter account on the off chance the agency announces new appointments to vaccinate.

“Today, when DPH sent out a tweet that there was a small number of openings, I ran so fast to my computer that my husband thought something had gone wrong,” she said.

Kim and her father waited 90 minutes at Dodger Stadium to get his vaccine and the check-in person greeted them in Korean. She’ll take her mother next.

Unlike others who see this next phase of the pandemic as another challenge, Kim is more practical.

“I think DPH is doing all they can. We could complain or we could pitch in,” Kim said. “We have a choice — this is my choice.”

But even with the arrival of the vaccine, the most complicated and radical variable in the pandemic remains: human behavior. Because for any of this to work, health officials must convince a fatigued populace that after a year of masks, physical distancing, and the tremendous sacrifices residents made in 2020 that the virus did not go away.

And the vaccine could become just another piece of background noise for communities hardest hit by the virus. The latest data from LA County Public Health shows that small pockets of the county are seeing far fewer vaccinations than more affluent neighborhoods. Essentially, the communities that need the vaccine the most — low-income residents and people of color who work essential jobs and lack access to easy and affordable health care — are either not being reached by the marketing or are unable to get appointments online.

Besides the online component and scarce resources to vaccinate, cultural barriers exist for low-income communities of color.

“One interesting thing are the concerns among Latino communities about coming together,” said Dr. Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, associate dean for Community Initiatives at USC’s Keck School of Medicine in a phone interview. Baezconde-Garbanati conducts research on how people will respond to health messaging regarding the virus and vaccine.

“There was a concern from someone in one of our focus groups who was worried about creating a new generation isolated from their family,” Baezconde-Garbanati said. “And to them, it’s not negotiable for some families. Instead of telling them to not get together, we need to focus the messaging on how to get together safely, because they’re going to get together regardless.”

To appeal to Latinos, the messaging might involve getting immunized for their elderly abuelo, for the kids, and the rest of the family, rather than for themselves.

For the Black community, the messaging will be different and may be more effective when it comes from faith-based leaders, said Baezconde-Garbanati.

In a region as diverse as L.A. County, with multiple languages and different groups with different sets of beliefs, the argument for the vaccine will necessarily rely on different talking points.

“The messaging will have to be segmented,” said Baezconde-Garbanati. “In my lectures, I tell students that you can give a child with asthma their medication. But you send them back into an environment that is overcrowded or they might be facing other poor living conditions. You need to be aware of those conditions.

“It’s important to understand people’s stories. Who they are? What their lives are like? So you can treat the person and not the disease.”

— By Nathan Solis, CNS

Like this:

Like Loading...

Related

Tweet This

Tweet This Facebook

Facebook Digg This

Digg This Bookmark

Bookmark Stumble

Stumble RSS

RSS

REAL NAMES ONLY: All posters must use their real individual or business name. This applies equally to Twitter account holders who use a nickname.

1 Comment

Of all the COVID risk factors, the top are:

Old, pre-existing conditions and male

Would like to see us follow the science versus reflexive ‘people of color’. Where is the focus on men…science shows quite clearly that white-brown-black men are at much higher risk. Not very woke, but very science